December 25, 2014

Selma

Frank J. Avella READ TIME: 5 MIN.

Like Steven Spielberg's "Lincoln," "Selma" smartly focuses on one brief, but pressing, period in U.S. history. Director Ava DuVernay ("Middle of Nowhere") ambitiously sets out to depict the sequence of dramatic events that changed and strengthened the civil rights movement, render an intuitive and intellectual analysis of that period, and make an uncompromising, truthful film. She gloriously succeeds on every level.

Avoiding the biopic pitfalls by not attempting the sweeping and usually futile notions of trying to squeeze a life and life's work into two or three hours, "Selma" delves into the psyche of Reverend Martin Luther King in a way no miniseries would, and sheds clearer light on President Lyndon Baines Johnson than any Tony-award-winning play could.

"Selma" doesn't try to canonize or demonize the two titanic figures at the center of the real-life story. The movie does its best to honestly describe and debate the obstacles these cordial, but contentious, men were facing, and what drove their decisions. They were adversarial allies very aware of combative times they were living in and very mindful of how these decisions would reflect on their respective legacies.

King is certainly the looming beacon in "Selma," but DuVernay never forgets the legion of lesser known heroic figures, as well as the roles played by the Southern bigots driven by ignorance and cultural conditioning (chief among them Alabama Governor George Wallace, played with racist fervor by Tim Roth).

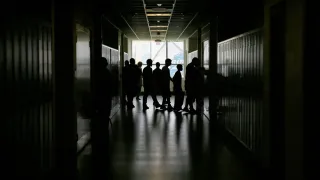

The film concentrates on the events that took place in the spring of 1965, when a bunch of brave people, led by Dr. King, attempted to peacefully walk from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to endeavor to change the voting laws. Up to that point in time, when blacks attempted to register to vote in Selma, they were repeatedly blocked from being able to do so. King and a host of courageous folks (led, in many cases, by students) knew that this was a do or die opportunity to make a bold statement and force the president to put forth the Voting Rights Act. Johnson, to his credit (via Kennedy's hard groundwork -- a fact that is sometimes forgotten), had just miraculously gotten the Civil Rights Act passed.

DuVernay keenly opens the film with King (David Oyelowo) and his wife Coretta (Carmen Ejogo) in an intimate moment as King prepares to accept the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. (Many revealing moments between the Kings are peppered throughout the movie, and give the film its soul.) The awards moment is intercut with a scene showing four little black girls in a Birmingham church chatting about what little girls chat about. We know what is about to happen, and a sense of horror and dread washes over us. DuVernay films the explosion in a strangely poetic manner that gives us time to contemplate the unconscionable act that has just taken place, realize how relevant the moment is, and prepare us for the unflinching cinematic juggernaut we are about to see. The stakes couldn't be higher.

As the narrative unfolds, we begin to understand King, his relationship with his wife, the cause he's fighting for, and the mood of the country (specifically the mood of the "cradle of the Confederacy") as the response to the marchers turns violent, despite the fact that the protesters have adopted a non-violent campaign. At the time, Americans had their TV programs interrupted and were bombarded with images of state troopers on horseback assaulting innocent people. Today we've grown quite accustomed to seeing horrors captured on video, but back then it was crazy shocking to witness such outright and shameless brutality.

As law enforcement continue to bludgeon and whip demonstrators in the streets, a devastating incident inside an eatery occurs; young Jimmie Ray Jackson (Keith Stansfield) is shot by a state trooper, at close range, despite the fact that he was unarmed. This image is one of the most resonant in a film filled with indelible images, as the camera speed slows down and the moment is held just enough to chill the viewer to the bone. (A tremendous note of irony: The shooter would later claim self-defense and would not be indicted by the Grand Jury.)

An angry King stirringly sermonizes, challenging the president (a superb Tom Wilkinson): "Johnson can send troops to Vietnam, but not Selma." He also calls on all citizens by saying that no one is blameless. "We must make a massive demonstration of our moral certainty."

The rest, as they say, is history -- and in DuVernay's hands it's an absorbing, illuminating history, dense yet concise, that packs one of timeliest punches of any film since "The Social Network."

Paul Webb has fashioned an intelligent, clean and well-structured screenplay that hits all the emotional beats without devolving into melodrama.

There are many rich moments: King calling gospel singer Mahalia Jackson after the killing of the four girls and asking to hear "The Lord's Voice"; blue collar Annie Lee Cooper (a touching Oprah Winfrey who co-produced the film) proudly trying to register to vote, only to be thwarted.

DuVernay and her gifted team of craftsmen weave it all into a cinematic wonder of a film that feels half indie, half big studio, all authentic, all complicated and messy (in the best sense). Credit Bradford Young for the arresting camerawork, Spencer Averick for his deft editing, Elizabeth Keenan for her period perfect costumes and Jason Moran for his poignant score.

And then there's the cast, specifically the two leads.

David Oyelowo fully embodies Reverend King, one of last century's most enduring icons, with the grace, dignity and charisma that made him a great leader but with the peculiarities, doubts and faults that made him a flesh-and-blood man. Oyelowo burrows deep to find the anxiety, uncertainty and fear inside his refined and polished presentation. The actor's commitment and immersion is nothing short of masterful.

Carmen Ejogo is his perfect match. Her Coretta may stand by her man but she also challenges him, complements him and questions him when necessary. In an uncomfortable yet captivating scene, Coretta confronts King about his infidelities and asks her imperfect spouse the most important question of all: "Do you love any of the others?" He's a deer caught in the headlights, but we believe his answer. Oyelowo and Ejogo create more sparks than any other onscreen couple in 2014.

"Selma" educates without being didactic, informs without appearing condescending and reminds without accusing. It is one of 2014's best films.

DuVernay is a smashingly gifted director with a visual and visceral style all her own. She never feels the need to bog down in the grandiose. If anything, she is subverting the bio-drama, treating audiences as intelligent, well-read beings. Or, at least, that they should be. Here's the essence of the man, the time and the battle. Experience it. Then do some homework if you have to and revisit it.

Recent events have demonstrated that we haven't evolved as much as we'd like to think we have, making "Selma" even more immediate and crucial.

The importance of this film cannot be overstated. DuVernay has reinvigorated Dr. King's dream of equality and gifted the viewer with an historical account pulsating with hope.