Oct 20

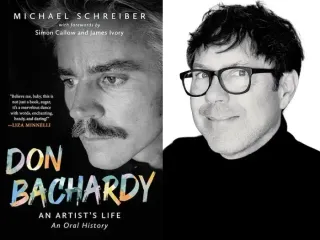

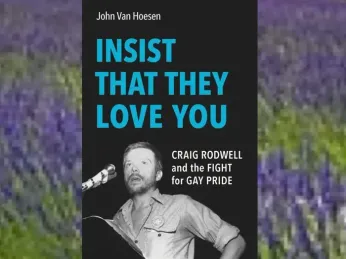

‘Insist That They Love You: Craig Rodwell and the Fight for Gay Pride’ – John Van Hoesen’s biography charts the gay activist’s life

Michael Flanagan READ TIME: 1 MIN.

As both a visionary and an activist, Craig Rodwell is probably best known as the proprietor of Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, or as one of the six people Martin Duberman interviewed for his book “Stonewall” as a witness and participant in the rebellion there. John Van Hoesen’s excellent new book, “Insist That They Love You: Craig Rodwell and the Fight for Gay Pride” (University of Toronto Press), reveals Rodwell (October 31, 1940 – June 18, 1993) as being much more, as a figure we can continue to draw inspiration from today.

Rodwell spent his first seven years in school at Chicago Junior School, a Christian Science school for “problem boys.” Rodwell qualified as his parents were divorced. By the time he was 14, he had already discovered his sexuality and had a steady boyfriend at the school.

After that, Rodwell hit the streets of Chicago and began cruising as a young teen. He claimed to be 17 and was apparently quite popular. This had mixed results. In one 1955 encounter, Rodwell met a man who told him about “One” magazine and “The Mattachine Review.” This set young Rodwell on a quest to find the Mattachine Society.

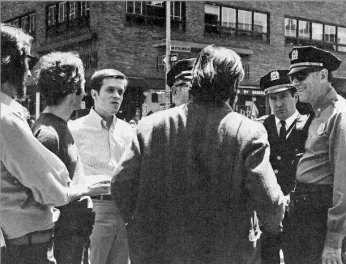

In a less fortunate encounter, he and his date were surrounded by police. Rodwell had been raised to always tell the truth and this did not serve him well. His date, 38-year-old Frank Bucalo, wound up with 60 days in Cook County Jail and was put on probation. Rodwell was nearly sent to a state reformatory, but his mother was able to convince a hearing officer to give him probation for two years and require twice weekly psychiatrist visits.

Big city

In his teen years, Rodwell heard Greenwich Village was where “queers” lived, so he determined to move to New York City. His ticket out was through ballet. Young Rodwell got a scholarship to Balanchine’s American School of Ballet in 1959. The move also put him in contact with Mattachine for the first time. At 18 he was told he was too young to be a member, but could attend their discussion group meetings.

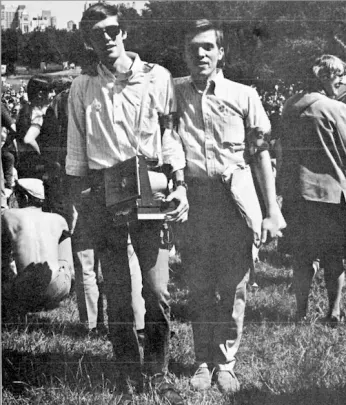

Two years later, while cruising Central Park, Rodwell met Harvey Milk. They soon became a couple. Milk was Rodwell’s first romance. The romance was ill-fated from the start, however. Milk of the early 1960s was not the activist of the ’70s; he was working on Wall Street. Following an STD and Rodwell’s arrest for a too-revealing bathing suit at Riis Park, the relationship ended in 1962.

Rodwell’s involvement with Mattachine increased and he participated in the first homosexual picket of a draft board in New York in 1964 and pickets of the UN, protesting Cuba’s persecution of homosexuals, and the White House, protesting Selective Service policy in 1965. After the May 1965 protest in D.C., Rodwell pitched the idea of the “Annual Reminder” protest at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, to remind the country of the status of homosexuals.

The first Annual Reminder was held July 4, 1965. Rodwell also announced the formation of Mattachine Young Adults, an outreach organization for people 18 to 35, in the New York Mattachine Newsletter in 1965.

On April 21 1966, Rodwell joined fellow activists Dick Leitsch, John Timmons and Randy Wicker at a “sip-in” at Julius Bar in Manhattan to protest the policy of not serving homosexuals alcohol in bars. Julius refused to serve them and that set in motion a Mattachine Society threat to report bars that engaged in discrimination. A week later, the State Liquor Authority announced it did not encourage discrimination.

Booking

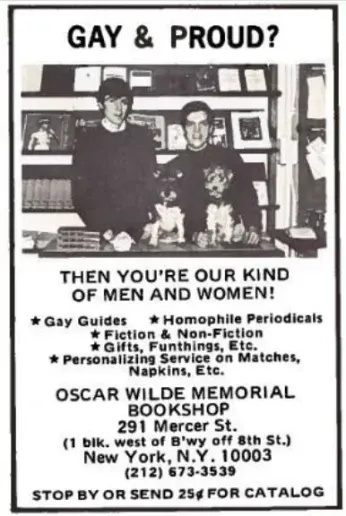

By 1967 Rodwell was pushing for Mattachine to open a storefront somewhere to engage the community. Although the idea went nowhere with Mattachine, he continued to pursue a community space. On November 16, 1967, with help stocking the shelves the night before from his mother, Rodwell opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop.

Van Hoesen’s book captures the impact and importance of the bookshop (never bookstore) in both pre-Stonewall New York and Rodwell’s life. Oscar Wilde offered cards and buttons, which probably seems mainstream now, but the bookshop was the first place this sort of merchandise was widely available.

It was also the first place that gay music was available in store, with an in-house DJ and albums like Zebedy Colt’s “I’ll Sing for You.” Van Hoesen notes that for patrons who bought the album, it was probably “the first time most people heard a man seriously singing love songs about another man.” There were signs in the window stating “Gay Is Good” and “A Bookshop for the Homophile Movement” from the 1967 on.

There was one thing that wasn’t available at Oscar Wilde, however: porn. Clark Polak, founder of Drum magazine (which the bookshop did carry) wrote Rodwell when the shop was opening:

“The mass of those persons who will be your customers want photographs and strong fiction. They do not want Mary Renault. If you continue to specialize in this way, you won’t make it.”

Rodwell, however, was firm on this. Perhaps it was because of the involvement of organized crime in porn. Perhaps it was because Rodwell wanted his shop to be welcoming to both lesbians and gay men. Regardless, porn was not sold there.

Community space

The bookshop acted as community space and a hub of activism, and drew comments far and wide. Van Hoesen includes excerpts of touching letters from teens coming out and a soldier in Vietnam who received his books via mail order. Rodwell spent hours responding to these letters.

It also acted as a community space for New York and New Yorkers who were coming out. Jonathan Ned Katz recalls walking around the block twice before getting the courage to go in when he first visited the bookshop. He would come back years later to sign copies of “Gay American History” in 1976.

Rodwell met his partner Fred Sargeant, who would later be Van Hoesen’s partner, in 1967 when Sargeant started coming into the bookshop. Sargeant would become the first manager shortly after he and Rodwell moved in together. As part of their role as a community space, they made sure that everyone who came into Oscar Wilde was greeted warmly.

He, HYMN and a riot

Rodwell began publishing the newsletter “The New York Hymnal” three months after opening Oscar Wilde. The name came from the Homophile Youth Movement in Neighborhoods (or HYMN), a group which Rodwell and Sargeant had formed to advocate for gays and lesbians.

In its first issue it addressed Mafia control of gay bars in its lead story. Featured in that article is a description of the Stonewall and how it spread hepatitis throughout the gay community. Keep in mind this article was published well over a year before the Stonewall riots. The book contains an appendix of Rodwell’s articles in the “New York Hymnal” from 1968.

The role of the bookshop and Rodwell and Sargeant in the Stonewall Riots is well documented in Van Hoesen’s book. After closing up shop and having dinner, they happened by the bar after midnight where a raid was happening. As the crowd exploded and resistance began, Rodwell shouted “Gay Power” and then he and Sargeant raced to a bank of phones in the Christopher Street subway and began calling newspapers.

As night turned to morning, Rodwell typed out a leaflet, one of two he produced that weekend. Saturday afternoon, Sargeant and members of HYMN distributed leaflets at Seventh Avenue and Christopher Street. Van Hoesen has reproduced one of these flyers “Get The Mafia And The Cops Out Of Gay Bars” in the book.

On July 4, 1969 there was another of the “Annual Reminder” pickets at Independence Hall in Philadelphia and the contrast between that and the Stonewall riots convinced Rodwell that what should come next was not another “Annual Reminder.”

Liberation

Together with Sargeant and their friends, Ellen Broidy and Linda Rhodes they came up with the idea for the Christopher Street Liberation Day, which would commemorate the Stonewall Riots in June 1970. With Broidy as their spokesperson, they pitched the idea to a meeting of homophile organizations in Philadelphia in November 1969. It was successful and word spread throughout these organizations as well as the fledgling Gay Activist Alliance and Gay Liberation Front. On Sunday June 28, 1970, 5,000 people marched up Sixth Avenue to Central Park.

The community caught up to Rodwell in the 1970s. Literary events at the bookshop are documented in the book, such as a visit by Tennessee Williams and signings by the likes of Edmund White and Jonathan Ned Katz. Van Hoesen reveals that the founders of Lambda Rising in Washington D.C., Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia and Gay’s The Word in London all looked to Rodwell and visited the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop when developing their stores. When Harvey Milk opened Castro Camera, his inspiration for the business as a community center came from Rodwell’s bookshop.

The best books about LGBT history are those which challenge our preconceived notions and inform us. “Insist That They Love You: Craig Rodwell and the Fight for Gay Pride” succeeds as one of these books. It demolishes the notion that members of homophile organizations were all wounded sorts begging for sympathy from the heterosexual world. It shows Rodwell as a community builder who worked with groups from the homophile era through gay liberation without pause.

As with most books published by academic presses, the book is impeccably researched. But unlike many academic titles, this book is both readable and enjoyable. The appendices, which include Rodwell’s writing for the “New York Hymnal” and “QQ Magazine” from 1968 to 1973, are a welcome addition to our history and will no doubt inspire other authors.

For anyone who has worn a button espousing gay or gender politics or has marched in a pride march, this is history you should read. Van Hoesen does not confer sainthood on Rodwell. He is described as cranky and difficult at various points in the book, much to our edification as history is often made by normal human beings who are sometimes cranky and not always saints.

‘Insist That They Love You: Craig Rodwell and the Fight for Gay Pride’ by John Van Hoesen, University of Toronto Press, $36.95, hardcover and ebook.

https://utppublishing.com/