October 16, 2017

To Kill A Mockingbird

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 5 MIN.

Harper Lee's 1960 novel "To Kill A Mockingbird" won the Pulitzer Prize, inspired a 1962 film starring Gregor Peck (for which Peck won an Oscar; screenwriter Horton Foote also won, for Best Adapted Screenplay), and was turned into a play by Christopher Sergel in 1970.

Gloucester Stage Company close out their current season with a production of Sergel's stage adaptation. Its themes of race hatred, a terror of African American male sexuality, white America's blend of rage and indifference, and innocence shattered make the production a timely one -- as much a commentary on the present day as Lee's novel was more than five decades ago. The fact that a Mississippi school district recently pulled the book from a junior high's reading list only underscores a growing sense that progress in the arena of race, to say nothing of the lofty ideal of "justice for all," isn't merely patchy -- it could very well turn out to be ephemeral, if not downright illusory.

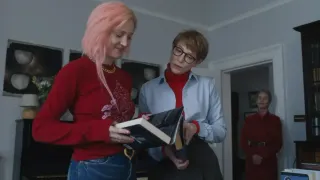

In a way, illusion is what "To Kill A Mockingbird" is about. The story adopts a child's-eye view of the world. The child in question is 10-year-old Scout (Carly Williams), and the world she lives in is a small Alabama town in the year 1935. As narrated by her adult self, Jean Louise Finch (Amanda Collins), the events Scout witnesses are arguably not suitable for children -- except for the fact, as Scout's father, a lawyer named Atticus Finch (Lewis D. Wheeler) points out, that what Scout, her old brother Jeremy (Nathaniel Oaks), and their friend Dill (Gabriel Magee) witness unfolding in the town over the course of that summer is the result of the society in which they live -- and will grow up either to accept, or strive to change.

The play's first act is all about setting tone, creating mood, and generating a sense of who these characters are and where they live. People in this Alabama town are poor; Atticus prospers as a lawyer, but he accepts nuts and other crops from his financially strapped clients as payment. His ideals are as pure as those of his children, but the real wonder is the deep-rooted decency that allows Atticus to hold on to those ideals.

His compassionate commitment to the tenet that everyone deserves advocacy compels Atticus to accept a case that's sure to affect his standing in the community. A young African-American man, Tom Robinson (Aaron Dowdy), has been accused of rape. The man making the accusation is an impoverished farmer named Bob Ewell (Cliff Blake), who claims to have seen Robinson "rutting on" Ewell's 19-year-old daughter, Mayella (Teresa Langford). The accusation by itself is enough for many townspeople to convict Robinson in their own minds of the crime; anticipating their response (and knowing that the local lawman, Heck Tate -- played by Thomas Rhett Kee -- won't be strong enough to fend them off), Atticus sets himself up with a chair and reading lamp in front of the local jail, intending to keep watch over Robinson's safety. Sure enough, a lynch mob arrives -- led by none other than one of the poor clients who pays Atticus with produce. Scout, watching along Jeremy and Dill, unwittingly intervenes, and only puts it all together later on. Such is her awakening to certain harsh truths about people -- even people she knows and likes.

Act II is, for the most part, a courtroom drama, and it's here that the play feels like it has snapped into focus. The presentation of evidence and the cross-examination are done in such a blunt manner that a contemporary audience knows well in advance what Atticus has in mind; we've all seen "Perry Mason," or "Law & Order," or some other legal drama, and in the presentation of the evidence and Atticus' careful case building we might feel a heavy hand and a pointing finger insisting on the conclusions we are to draw. Still, director Judy Braha has such a sure grasp of the material, and the cast are so committed -- including the young actors, whose characters, having taken a keen interest, are among the spectators -- that the production creates and sustains a sense of suspense.

The excellent cast includes Cheryl D. Singleton as Atticus' stalwart maid, Calpurnia, and Thomas Grenon as the fiercely intelligent Judge Taylor. Douglass Bowen-Flynn plays Boo Radley, a recluse the children try to befriend; too shy to met them in person, he leaves gifts for them in a tree. Bradley's character is almost more palpable in his absence than it is when he finally does appear, and Bowen-Flynn captures his paradoxical qualities with a poignant performance. (He also portrays the prosecuting attorney, a man who hesitates not at all to use the racist assumptions of the jury to his advantage.) Stewart Evan Smith plays Rev. Sykes, rendering a small role with layers of weariness and compassion that match nicely to Atticus' own.

The play's design work is spare but not stingy. Jon Savage's set design in particular possesses a rough and rudimentary feel that allows the space to serve as courtroom, back yard, town street, and every other location the play requires. So rustic is the set -- and so smooth the design's overall effectiveness -- that the courtroom's use of barrels and boards for furnishings (judge's bench, tables for the prosecution and defense) seems natural and we don't spend time nit-picking over it. All it takes are a few elements to roll out from the wings -- a screen door, a swing made out of a tire on a rope -- and we've left the complex, and considerably darker, world of the adults for the children's back yard paradise.

John Malinowski's dramatic lighting design pairs well with the set, while David Wilson's sound design is unobtrusive and effective. Chelsea Kerl's costumes, similarly, evoke, rather than imposing, the place and time, and summon the characters rather than merely swaddling the actors.

The times being what they are, the greater Boston area's theater scene has been full of work that's cautionary, satiric, or grimly advisory. "To Kill A Mockingbird" feels like something a little different, though -- both a punch in the guy and a mournful sigh at the ways we, as a nation, sometimes seemed determined to cling to our failings.

"To Kill A Mockingbird" continues through Oct. 27 at the Gloucester Stage. For tickets and more information please go to http://gloucesterstage.com/17-6-to-kill-a-mockingbird/