April 2, 2018

Sequence Six: On Account

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 29 MIN.

"Look at them," Henry sighed.

Emily, keeping pace beside him with delicate, careful steps, didn't lift her eyes from the sidewalk. She was far too afraid that if she did she might stumble over a fissure or catch a heel in a pothole. It would be entirely too easy, at her age, to shatter a hip - and she knew what that would mean. She'd seen it all too frequently among her cadre of life-long friends, a group that was steadily dwindling in number: A major broken bone, be it hip or leg or arm, was the first domino. Once in motion, whether it was quick or slow, the sequence of events and the end result were the same: Decline, dementia, death.

But she didn't need to look up to know what her husband was talking about.

"Henry," she chided, "remember yourself. You are eighty years old, for heaven's sake. Don't go ogling young girls. It isn't fitting."

But Henry, she was surprised to find out, had not been ogling girls at all.

"Them," he said, guiding her to the edge of the path and then pointing with a thin, knottily veined hand. The skin was blotched, Emily saw, and the tendons prominent. Her husband's hand was the hand of mortality itself, reaching steadily, reaching toward the both of them...

Sighing, she lifted her eyes away from his outstretched hand and looked toward where he was pointing. A group of five or six youths - in their teens or twenties, it was hard to tell any more - were strolling in a tight little group, talking loudly, tussling and laughing.

"You remember?" he asked her. "You remember when we were their age?"

Emily did, far better than she remembered the last few years or even the last couple of decades. The past stretched behind her, cavernous and yet also compact. How had so much time gone by? What had she been doing all those years? She could remember some things quite distinctly - holidays, weddings, the births of children and grandchildren, the deaths of friends and cousins and siblings. She could remember certain things about her years with the law office - contracts, celebrations, the sudden death of Mr. Finch, who had been one of the partners, and whose nephew had taken his place. But so much else had slipped her mind - time and action, effort and accomplishment that all merged together colorlessly, or else evaporated. Like dreams, she thought. Like recurring dreams that superimposed into one version of the dream, one authorized edition. Or else singular dreams that lingered in the memory for a while, made for an amusing story, but then disappeared.

Like her youth, and Harold's.

"Yes, dear, but now we are old," she told him. She tried to resume walking but he remained rooted to the spot, his hand on her arm.

"Look," he whispered.

She turned her eyes again to the group of young people. Some sort of banner seemed to be fluttering over their heads...

No, not a banner, she realized. A holographic supertitle. YOUNG AGAIN, the supertitle read, as the jovial banter among the young people continued. A girl jumped laughing into the arms of her boyfriend, and he spun her around. The supertitle changed to: FIND OUT MORE. Then, the legend changed a final time: NEURONEXUS.

It was the name of a company Emily had vaguely heard of. A sudden line of distortion cut through the sight of the young people and the group seemed to wobble and then vanish, only to reappear at the other end of the park. Walking and chattering just as they had done before, the cluster of fit, happy young people seemed to move across the green expanse, shadows of trees falling over them in a natural-looking way, but they weren't really there. They were a holographic projection. They were, in fact, a commercial advertisement.

Next to her, Henry sighed. His hand fell away from her sleeve. "Why?" he asked, sounding plaintive. "Why do we have to be old?"

"Time goes by. The flesh of the fruit withers. It's the way of things," she said, reaching to touch his arm in a consoling gesture.

He seemed to shudder. Was it a sob? A tremble of rage? She didn't risk a glance at his face. They walked slowly together. Behind them, the commercial played to its conclusion and then re-set. The same shouts and laughter drifted through the April air still again.

Then the program seemed to go into rest mode, because the clamor faded away.

Fading like every other evidence of life, Emily thought. Some day these bones of hers would no longer move of their own accord. Some day...

The ad was sure to resurrect Henry's complaints and wistful longing for things they couldn't have. In this age of clones and half-clones and memory shares and refinements both physical and mental, it seemed that anything was possible: Eternal life, restored youth, beauty that never slipped away with time. Happiness. Productivity.

But only for those who mattered. Only for Owners, the people with money. Not for workers like herself and Henry, and certainly not for people of a certain age - people who remembered what it had been like when people didn't own each other, a time when many people enjoyed prosperity - far more than the tiny sliver of society who now possessed everything, all the wealth, and, with it, all the influence. They had called it something quaint and a little ridiculous back then. Emily couldn't remember. Some kind of class. Center Class? Central? Medium?

It didn't matter. That was a profoundly different time, before the Gender Laws and the Faith Laws and the Family Laws had crept up like snaking ivy vines, choking everything and making any move a potential affront. Who, Emily asked herself, would want life eternal when life had gotten so crazily uncontrollable? They were lucky that Henry was the sole survivor of his brood of siblings. That made him the family's patriarch, and endowed him with literal power of life and death over the family's younger men and all their women. Since their children had all forsaken life partnerships and opted to reproduce using half-clone technology, their grandchildren weren't just under Henry's purview; they were the property of their parents. And, since their parents were under Henry's legal control, the grandchildren were, for all practical considerations, Henry's possessions.

Not that they had wanted any of that. Not that any of it made the world a better place. It was a cruel world now, a punitive world that celebrated selfishness. Emily focused on the path and tried to remember happier things.

An uplifting thought came to her at once. "We have a visit with Thalia and Douglas and the kids," she said.

"They are coming?" Henry asked. "When?"

"Oh, you remember. We talked about this. They're coming today."

"Today! But I don't want to have company today."

"They're coming at four," Emily said. "We talked about this yesterday, and the day before, and Monday, and last week. She's making dinner and bringing it with her. It will be very nice to see them. And the children love you."

"They don't," Henry said. "They love you. No one loves me. Not even you."

"You need a nap," Emily said. "You're getting to be an old man."

***

Thalia and Douglas and their kids left at six thirty. By quarter after seven Emily and Harold were settling into bed. They occupied twin beds; he preferred his own bed because, he said, he hated the thought of his constant uncomfortable shifting keeping her awake. Well, it was just as well, Emily thought. They were too old for sex.

Harold, in his blue striped pajamas, lay heavily on his back, staring up. She couldn't see his eyes through his glasses. Was he asleep?

"You know," Henry said suddenly, "we don't have to do this."

So he was talking, but that didn't mean he was still awake. He did talk in his sleep sometimes.

Emily waited to hear what else he might say. "Emily?" he asked. "Did you hear me?"

"Yes, I was waiting for you to say more," she said -- truthfully, she reflected, smiling to herself. "What do you mean? What do we not have to do?"

"Keep getting older. Getting weaker, losing our minds, becoming irrelevant," Henry said. "What I mean is, they say the bugs are all ironed out."

He could have been talking about the new phones, or the direct cortical stimulant devices they called cerebrexes, or the memory share technology that was starting to upset all sorts of apple carts. All of these new technologies were things they had talked about recently for one reason or another. Wouldn't it be nice to leave some memories to their kids and grandkids? Memories of the old days? Wouldn't it be prudent to create an incontestable Last Will and Testament using the cerebrex technology? Or find a cerebrex recording made by a young person doing young person things... rock climbing, eating spicy food, having hot and sweaty sex? There was a real market for this sort of thing among people their age, though there were also some health risks associated with sampling the more extreme adventures. You could still die of a heart attack climbing Mount Everest even if in reality you were sitting in your armchair.

But she knew at once what he was talking about. That damned ad in the park. Real and palpable youth. Golden, artificial, unattainable...

"The problem isn't the bugs in the motor skill software," she told him. "It's the cost. We talked about this, Harold. You keep bringing it up. We just don't have the money for two... or even one... replacement bodies."

"Strength. Clarity of mind, sharpness of senses," he said, ignoring her. "A genuine transfer of the mind - not just a copy of the mind, but the real you, taken from the dying shell and put into a fresh new body."

Yes, because the relevant brain tissue was grafted onto artificial neurons and over time the natural process of memory formation - and memory access - replaced the dying neurons with new ones, synthetic ones, indestructible and ageless. All of life was a process of transitioning, molecule by molecule, from what you had been to what you would become. The gradual upload process was the same thing, only it was a transition from organic to Siliconian flesh. The unnaturalness of it made Emily shudder.

They said you never even felt a difference, never noticed as your thoughts grew more coherent and your memories more reliable... until your thoughts were whirring along lighting quick and you never forgot a detail of anything you saw or heard. Better than you were before. Better... stronger... faster...

She chuckled dryly. "I don't think I would like that, even if we had the money."

"There might be a way," Henry said. "I heard about some possibilities."

"What?" Emily asked him. "Sell the house? Pay them our life savings? We still wouldn't have enough. We have money to live out our natural lives, my darling, but not to resurrect our youth."

Henry didn't respond to this.

"It's okay," Emily said gently. "It's the way of things."

"I made an appointment," Henry said, as if she'd not spoken.

"An appointment?" Emily asked, shocked.

"After our walk this afternoon. I went to the NeuroNexus virtual office. I read about some new financial options. I think they can help us."

"Help us what?" Emily said. "Become Siliconians monsters?"

"Come with me tomorrow," Henry said. "I won't order you, but I'm asking."

"All right," Emily sighed. It was going to be a waste of time, but better she accompany him and stop him from signing away their house or their savings or - who knew, maybe their vital organs. "All right, love."

***

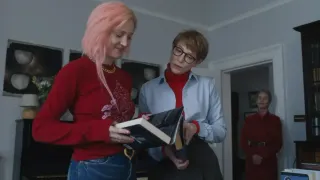

"It's not as expensive as you might think," the Neuronexus rep told Henry. Like the young people in the park on the previous day, she was present as a holographic image - she looked real enough; she looked solid. Henry and Emily sat on their sofa listened attentively as she outlined various plans and packages. "The thing is," the rep summarized, "we at Neuronexus understand that everyone wants to live. And we believe in the old principles of life and liberty for all."

Henry chuckled. "What a crock of shit that turned out to be," he said.

"Well, we are not a political entity," the rep said, smiling. "We're a business. We deal in service and products, not in philosophies. All the same, we believe everyone who wants to live should be able to. It's really just a matter of human values, and human decency."

"Not in a Siliconian shell it isn't," Emily interjected.

The rep turned her head to look at Emily. It was just like the young woman was sitting there with them in the living room. They were making eye contact, they were conversing.

Emily had no idea how any of it worked. It was easy to forget that the rep was actually not there. She was kilometers away in an office or a projection suite somewhere.

"I know you can't tell," the young woman said, "but I'm an AI, and I don't even have a body. A Siliconian physiognomy, from my point of view, isn't such a terrible thing. It's part of what I was talking about - liberty."

"I'm sorry," Emily said. "I didn't mean... well, I know that sounded racist. I didn't mean to put you down."

"Please don't worry about it," the young woman told her. "My point is, I'm just as alive as you are. Organic, Siliconian, physical, virtual... there are many ways of being alive these days. Have you considered a purely virtual conversion?"

"Become Psyclones?" Henry said, aghast. "Certainly not."

"The virtual world is much more flexible than the physical world, and you can simulate any physical environment you wish. Though," the rep added, "most people, even the skeptics, take to the endless possibilities of virtual life quite quickly."

"No," Henry said. "Anyway, the problem comes back to money, and the Psyclone servers cost - how much every month? No, with new bodies we pay once and we're done."

"Very well," the rep said, her smile never faltering. "Of course, as you have noted, Siliconian anthroframes are expensive. But the market keeps evolving, and recent advances have made it possible for even non-Owners to purchase durable bodies of their own."

"How?" Emily cut in. She'd been waiting for this. Now the truth would come out - the whole snake-oil con job was about to be revealed. It might be cloaked in jargon and technocratese, but Emily had worked in software for decades and her focus had been legal AIs. She knew more than a little about both law and synthetic life sciences.

The rep was looking at Henry again. Smart, Emily thought. The rep knew Henry was more interested. No doubt she could smell his desperation. AIs weren't dumb, and they didn't lack insight. Emily herself had pushed for the innovations that made it possible for synthetic consciousness to include a rough form of intuition, and that breakthrough was now decades old. It had surely been refined since then.

"Synthlife science has progressed at astounding speed," the rep told Henry. "As a direct result, organic life science has also progressed. The two have started to merge. We can now create biological organisms using techniques similar to modern Siliconian construction. The first autoconstructs were modeled on the mechanisms that enable organic organisms to self-assemble. Now, with the high degree of refinement that we've achieved in the field of autoconstruct technology, we find we can apply many of the same techniques and principles to organic life."

"You can build organic bodies?" Emily asked, shocked.

"Not yet," the rep said, sparing Emily only a brief glance. Her gaze returned to Henry. "But we can transfer organic minds to preexisting organic bodies."

The rep paused. Henry and Emily looked at each other, wearing mirroring frowns.

Emily voiced it first. "You mean you can make it possible for a sick or elderly person to move into a younger, healthier person's body."

"That's correct," the rep said brightly, this time not even looking in Emily's direction.

"You want us to occupy someone else's flesh?"

"Oh, no," the rep laughed, still fixated on Henry, selling to him and him alone. God damn her, she knew he was the patriarch, Emily realized. There was more to this than economics. Some sort of tricky legal issue had to be involved. "Organic-to-organic transfer is still very complex and expensive. To be frank, you fall far below the requisite asset bracket to apply for the procedure. However," the rep added, "you do possess something that our higher-end clients need. And if you provide that necessity, a trade can be arranged."

"What sort of trade?" Henry asked dully, as if from far away. Entranced by visions of a new young body, Emily thought.

"You have a number of healthy children and grandchildren," the AI said.

"You want us to trade you our own family?" Emily cried in horror.

The rep looked at her then. She didn't say anything. She blinked; that was all; a blink that flickered over her innocuously smiling holographic face, her flawless face. It was, Emily thought, unutterably grotesque.

The rep was looking back at Henry now. She said, "The terms are simple, and they are more than fair. Very generous, actually. I presume you would want two Siliconians bodies, Mr. Tsu, one for yourself and one for Mrs. Tsu."

"That's right," Henry said faintly.

"We require three healthy organic specimens under the age of thirty, but over the age of sixteen, for each Siliconian anthroframe we provide," the rep said. "We'll even personalize them so that they look, sound, and move just as you are familiar with... or, if you prefer, you can upgrade for no additional cost."

No additional cost? What could they possibly want had there been a surcharge? The family pet? Emily struggled to rise, hot and almost dizzy with indignation.

"Are you uncomfortable?" the rep asked Emily.

"I am scandalized," Emily said in a brittle, icy tone.

"I understand," the rep said, and she actually looked sympathetic. "But," she continued, turning back to Henry, "you do have three grandchildren in their twenties, and a number of great-grandchildren, Mr. Tsu, and one of your granddaughters is married... to a Mr. Douglas Framen, correct?"

Henry said nothing. Emily saw at once where this was headed. Douglas came from an even poorer family, and he wasn't close with any of them. His patriarch could probably be persuaded to sell him, and sell him cheaply.

"Your eldest great-grandchild is sixteen," the rep said. "She's old enough. The other great-grandchildren are too young, but of course they offer something in the way of future prospects."

Emily was still looking at her husband, aghast that he wasn't protesting the rep's monstrous sales pitch. Pay for their new artificial bodies by selling the bodies of their descendants - bodies that would then be taken over by diseased and superannuated Owners looking to extend life and vitality? She felt sick; she felt unreal; she couldn't believe this was happening.

"You have enough young family to meet the compensation requirements," the rep said. "The fact that your grandchildren are all half-clones makes things easier still, since half-clones have no personal rights to conflict with patriarchal privilege. The fact that your sole eligible great-grandchild is not a half-clone is irrelevant since she is the offspring of a half-clone, and therefore has no personal rights either. Only your children could contest you on this, and any legal case they would bring would be derailed from the start since they are not eligible and would not be part of the transaction."

"I won't stand for this," Emily said. "Henry, tell her to leave."

"I've told you want you needed to know, so it's convenient to end the information session now," the rep said. "Let me just provide you with a prospectus that provides everything I have told you as well as a wealth of additional information."

A new document pinged its arrival via aethermail to Emily's personal saneframe. Henry would certainly have received the same mailing.

"I'll let you discuss it," the rep said. "But take too long. Mr. Framen is twenty-eight years old. Almost twenty-nine. He won't be eligible for trade for much longer. As it is, his actual worth is much less than it would have been a year or so ago, and it declines even more sharply once he passes his twenty-ninth birthday."

The rep faded out, leaving them alone in their living room.

"There is no way I am agreeing to this," Emily said. "And I can't believe you would even consider it, either, Henry."

But the look he gave her was far from reassuring.

***

Over the next few months Henry pressed his case. Emily made no bones about her objection to the very idea that she and Henry would trade the children of their children to NeuroNexus in exchange for synthetic bodies. "They want our flesh?" she cried. "They want our flesh in exchange for machinery?"

But Henry saw things in a different light - not from the point of view that these were people, precious people who should be allowed to live their own precious lives, but from the perspective of a patriarch, someone whose legal control over others was close to absolute. It was a perspective that informed Henry's idea that their existence was his to do with as he liked.

"It's very much a fad with the Owners," Henry told her. "Fads create value. But who knows how long the fad will persist? Biological bodies are today's hot commodities, but maybe tomorrow it's the anthroframes that the Owners will want to purchase. Then we have nothing left to offer to finance our own artificial bodies."

His dry rasping voice, the voice of an accountant talking about numbers, filled Emily with rage. They weren't talking about numbers. They were talking about the flesh of their flesh - the blood of their blood -

"If we are going to do the trade, we should do it now," Henry continued, oblivious to Emily's outrage. "And anyway, like the rep said, it's not long before Doug turns twenty-nine."

Oh, the fool, the selfish old fool! How could he have become so morally crippled? How could the law permit someone so morally deficient to remain in charge of other people's destinies, their lives and health and bodies? But that was the nature of the law; it had been that way, in one respect of another, for centuries, from the early days of America when race distinctions provided a rationale for slavery to the political tumult of Emily and Henry's own youth, when male lawmakers sought to exerted the force of law over women's bodies and, later, career decisions. Those edicts of control had finally been codified in the Gender Laws, and the Work Laws, Faith Laws, and Ownership Laws only reinforced and steepened the license that the powerful had legally assigned themselves over those without resources or political pull.

Their arguments grew bitter, then silence fell over their unhappy house when Henry revoked Emily's access to the aetherweb, lest she send a message of warning to the children. Then he restricted her permissions to travel, confining her to the garden, the local church, and the small park up the street. Were Emily to set foot beyond those locales unaccompanied by Henry, her saneframe GPS would alert the central garda tracking grid and an officer would - solicitously, gently, but firmly - guide her back to her approved place. It filled Emily with rage, and with a sense of betrayal; all throughout their life together she had entrusted herself to Henry's care, as the laws tightened like a noose around her, sure that he would keep her safe. Now he was using those laws the way they had always been intended: To deprive her of her personal agency.

If Henry could not earn Emily's approval for his plan, he settled for her silence. Once in a while he would offer some gesture of reconciliation, but it never involved a departure from his gruesome plans for their family. "Once we are young," he would tell her, "you'll see that it's all been worth it."

Emily doubted Dorothea, Adnan, or Pru would agree. When they found out their father had sold their children for his own benefit... Emily could not even pursue the thought. It was madness, but Henry had the full force of the law on his side.

Six weeks went by. The night before a small squadron of orderlies were due to fetch the both of them to the NeuroNexus facilities, Emily lay rigidly in her bed, tense with anger and terror and grief. Why didn't she rise and kill him, the foolish old man, where he slept? The tyrant! Why didn't she at least find a way to take her own life? It might shake Henry from his monomaniacal zeal for a new life in a fake body. At least it would reduce the price Henry would have to pay, because with Emily dead he's need only one Siliconian replacement for his own aging flesh...

When daylight slowly dissolved the night's gloom, Emily was still staring at the ceiling, but now she was admitting it to herself: she was powerless before Henry's whims. And, when she thought about it more deeply, it was a relief. She saw, and shuddered at, the base, selfish truth of it: Like her husband, she wanted to live - wanted so badly to be young again, with life unlimited before her, that she was willing to take the lives of those to whom she had given life.

And, she thought, it wasn't as if they had made themselves deserving of that life. Half clones for children? That wasn't a family! Hadn't she taught them better than that? She knew she had. The truth was, they were selfish and corrupt; they had made immoral choices; Henry was right to take their lives and trade them in for something that reflected real; values - something truly worth while...

She lay there seething, shaking, astonished at herself. Those rationalizations were nothing but a way to live with herself for the many years... maybe centuries... ahead, Emily thought. She imagined herself as an AI, like that receptionist, imagined looking herself square in the eye. Tell the truth, she said, and her holographic other, now young, turned to her with ineffable grace, with the unencumbered mobility of youth. I see you've finally come around, Emily's other self said, and Emily came awake with a great start.

She'd fallen asleep. She'd dreamed.

But the transition wsa no dream. She'd accepted Henry's decision; she'd accepted its consequences, even its inhuman cruelty and monstrous selfishness.

And she was about to live again, live forever.

Suddenly, Emily found that she was no longer sick to her stomach at the thought, nor dreading the procedure, Suddenly, she just wanted to get it over with.

***

The medical and mechanical process of being made young and immortal wasn't something that could be done remotely. Emily and Henry would need to take a NeuroNexus transport to a company facility. They didn't take anything with them; they stood empty-handed in the front yard waiting for the transport.

Then they rode in silence, sitting in the back seat of a vehicle that looked like a limousine but soared swiftly through the air, riding a cushion of electromagnetic energy above the HardGlas streets.

Henry, Emily noticed, was sitting rigidly, not looking at her - ashamed, she thought. They both should be. They both had so much to be ashamed of, as much as any mortal with more than eighty years' worth of deeds and thoughts and words and intentions to account for. And now, adding to that great moral ledger, this - this horrendous debt to all that was decent.

Guilt stirred deep within her. Then it disappeared, replaced by anticipation. Then Emily felt numb. It was all too much; it wasn't even real...

She reached across the seat and found Henry's hand. Gingerly, he returned the clasp of her fingers, and then looked at her. They held each others' gaze, lovers at the end of the world as they knew it.

"Will this really work?" Henry asked her. "Will it really be us? Will I really have you at my side forever, my love?"

She squeezed his hand reassuringly.

"And what will happen to the children? Will they truly be preserved, maybe one day returned to life in new bodies like our own?"

Emily had read the prospectus the rep had mailed her. Its cheery text had offered reassurances she had not quite bought into, promising that when the younger family members' bodies were readied for new owners the relevant brain mass containing individually distinct identities and memories would be set aside, preserved in some sort of suspended animation. Those brain sections had to be removed anyway, in order for the wealthy new owners to take possession of the bodies.

Emily wondered about neurological regeneration, tissue rejection, the issues of a more primitive time. Those had all been overcome. Human flesh was really just another material now, a new medium to sculpt... to improve... to engineer... to trade. Their grandchildren's neurological tissue would be retained for up to fifty-four years. Then, for the appropriate fees, they could be given new bodies of their own, if anyone cared to pay for them.

In theory, that would be Emily and Henry's duty. But Emily doubted that would ever be the case. The niceties of the law were no longer so very kind except in words and flourishes. The law had once protected everyone, or at least aspired to. Now it had become one more barbaric implement, barely covering the fangs and claws of human viciousness.

Emily's eyes wandered to the limousine's window, her face taking in dead farmlands, ruined buildings dotting the landscape.

It was all about survival, she reflected. Survival of the fittest. Of the lucky. Of the pitiless.

***

"There," the technician's voice said. "There, yes. Better?"

Emily opened her eyes.

"The grafting went flawlessly, and I have to tell you - your husband selected a very attractive anthroframe," the tech said. She was young and dark of complexion. She had a faint accent. She was Indian, Emily thought, or Pakistani...

Some sort of mental circuit kicked in just then, her thoughts racing through a hoard of knowledge Emily had forgotten she once possessed. Or had they given that to her? Was this a database that came built into her new Siliconian body and brainstem?

The tech's name was Amrita. She was a current-generation Siliconian, an anthroframe model - an autoconstruct pre-devised to look and sound the way she did. Siliconians, Emily realized, like organic human beings, could have ethnicity.

And these thoughts, this sudden knowing... this was not information contained in Emily's artificial neural complex, which already had congealed around and integrated with the implanted remnants of her organic brain. This was something beyond her own mote of consciousness - like a vast ocean stretched before her, something felt, something enormous and majestic, resonant and perpetual... the great wealth of all human knowledge, ready and present and accessible at will. This was instant and comprehensive access to the aetherbase. It was like tapping into the base using her old saneframe, only... only her comprehension, once so slow and narrow, once needing hours of days to build a complete picture of relevant information, that comprehension was thousands of times faster and millions of times wider.

It was like seeing one's home village from the top of a nearby mountain for the first time. It was like... Emily almost gasped, but that response was not part of her pre-programmed autonomous reflexes. At least, not yet. But the shock and delight of it was unparalleled. Her sudden ability to access limitless information on virtually any subject was unlike any sensation she'd ever had.

The tech helped her get up from the recovery table, a physiognomically-contoured medical couch that monitored the functions of her body and braid and stabilized them as needed. She's been lying on the table for almost twelve hours. Her body had come online and her brain... her mind... had integrated into its new home without complication. She needed no extra recovery time: The table signaled her readiness to get to her feet and begin a new life.

Her old clothes were never going to fit her, Emily thought, pausing in front of a full- length mirror to scan herself up and down. She was taller than she'd ever been before. She looked perfectly human - and perfectly beautiful. She ran a hand over her own skin, feeling its texture and temperature and contour with superhuman acuity.

"Your three primary senses are much superior to their organic equivalents," the tech told her on a quiet, pleasant voice. Emily could hear every syllable distinctly. In fact, she could hear a range of sounds, none of them particularly loud, in the environment, from the air circulation to various small chimes and auditory notifications emanating from the room's equipment. Colors and shapes and light were all clearer to her now, also; her artificial eyes were seeing things in minute detail. And from small slit-like windows set high in the ceiling - from them there entered into the room a new color, unlike anything she'd ever seen before. Like blue, like purple, but brighter, deeper...

"Ultraviolet?" she asked, staring at the narrow windows.

"There is a slight increase in the ranges of your visual and auditory perceptions," the tech said, retrieving a bundle of neatly folded clothing from a cart. "It comes in quite useful. If you like, or if needed," she added, "your vision can be upgraded to see well past the light spectrum typically visible to the organic human eye."

Emily nodded, saying nothing, marveling at her ability to see and hear and touch. Then something else the tech had said registered for her. Three primary senses? Shouldn't there be five?

"What about taste?" Emily asked. "What about smell?"

"Two perceptions of essentially the same stimulus feed," the tech said. "You have to real need for either. You'll discover that you do have the ability to chemically sample the air; it's useful, in case there's a fire, to be able to detect smoke. And you'll be able to detect carbon monoxide, radon gas, all sorts of things. That constitutes a sense of smell of a sort, I suppose. But you won't have a sense of smell in the regular human way. And unless you undergo a fairly extensive refit you won't have a sense of taste at all. That could happen, of course, if you end up becoming a gourmet chef, but otherwise there's no utility in it. It would be a waste of processing power. So, no. No smell nor taste."

"Why not? I thought these bodies were supposed to give us renewed life."

"You're alive; you're strong; you are able to see and hear and feel with exquisite sensitivity; and as time progresses and your organic neurological tissue integrates with - and then is replaced by - synthetic neurons, you will be able to think much more clearly, understand much more easily," the tech said. "For all practical purposes, this is a new life. But it's not a perfect replication of human life, and neither is it mean to to be. Siliconians have no need for food. You won't feel hunger or thirst, you won't have food creavings. And aside from some basic uses, a sense of smell is similarly expendable. What could you get from it? You won't have the emotional responses to smell you did in your earlier incarnation. And in any case, strong emotional responses are similarly redundant for life in the Siliconian mode."

The issue around food, Emily could understand. Siliconians had their own self-contained power generation technology and didn't need to rely on chemical fuel like food. But what was wrong with allowing her to taste, for the sake of pleasure? And what did it mean that she would lack strong emotional response?

Then Emily understood - perhaps thanks to her already enhanced mind, or maybe thanks to her native intelligence. Emotions were largely based in hormones and brain chemistry. She still have organic brain tissue, but not from the brain regions that dealt with emotions. And she had no adrenal glands - nor any other glands.

Emily paused, gripping the bundle of clothing the tech had given her, and examined her emotional state. What she had taken for curiosity, for wonder, for relief... they weren't, really. They were intellectual replacements for those emotions, lacking the instinctual depth and dive of the real thing.

Emily searched for the terror and guilt that she'd felt before the procedure, an agony of conscience and horror that had pursued her, fading in and then dissipating again, right to the brink of her former life; she felt tendrils of guilt and doubt even as she was going under general anesthesia. Now those feelings were gone, gone with her organic self. Dead, she supposed.

"Put on your clothes," the tech said. "It's time to go out and meet your husband."

***

The clothing the tech provided was sober and practical. Emily gave some thought, in the back of her mind, to the fashions she would be able to procure for herself, in her new, slimmer, taller size. This nondescript attire would do for now, she supposed.

Henry, when she saw him, was dressed in similar clothing. That must be Henry? The man who already stood in the room to which the tech led her? Like her, he was now tall - taller than he used to be - and handsome, with a face that bore no resemblance at all to Henry's old face. But the way he stood - that was Henry. She walked over to him, and it occurred to her to wonder where the rush of happiness and love was. She remembered again: No hormones. No emotions. She had the capacity for aesthetic assessment, and that was similar - if in a remote way - to emotion. She didn't love Henry. Neither did she hate him for the things he had done, the choices he had made, the all too frail man he had been.

"Henry," she said.

"Emily," he responded. "You're beautiful."

"A touching reunion," the rep said. She was no more physically real here in the facility than she had been in their living room. As before, her body was merely an image, flawlessly manifested but possessing no material qualities. She had looks, but no mass, no temperature, no... No affect, Emily thought, before realizing that personal affect was something she herself had probably all but lost. Like Henry, she retained her particular posture and way of moving. But the rest of it? The slight thing, the animal thing that made her recognizably human? Where was that? The rep had it, to a degree, Emily realized, which made her wonder whether there were possible upgrades that could allow one, by bits and pieces, to reclaim something like one's former humanity.

Before Emily could ask the rep or the tech about this, a young man and woman entered the room. They had a definite human affect: The man exuded coldness and arrogance, and the woman a sort of superiority of manner and a gloss of vanity that Emily had known in certain schoolmates when she had been young.

"Is this them?" the man snapped, glancing at Emily and Henry.

"Yes," the rep smiled. "They are ready for you to take possession."

"Take possession? Of us? Explain yourselves," Henry said.

"It's simple, asshole. I own you," the man told Henry, raking him with an irritated glance.

"How do you even say such a thing?" Henrry responded. "I am a patriarch. You cannot address me in that manner."

Ego? Emily thought. Or the habit of ego? What was she seeing in her husband at this moment?

The man glared at Henry. "You'd best learn your place. I won't tolerate this kind of insubordination."

The woman, meantime, had gravitated to Emily. "Too pretty," she announced. "Can you do something to make her plainer?"

"Not at present," the rep said, still as cheerful and bright as ever. "Short of maiming or scarring her, that is."

"Knock it off, Madge," the man said, turning to his wife with the same impatience he had shown Henry. "She's fine. And don't you think about defacing her, or I will deface you."

Madge's face hardened, and she gave Emily a last hateful glance before turning her gaze away.

Henry, uncowed by the man's swaggering display, simply stared at him.

The rep addressed Henry. "You must realize that since you are now legally Siliconians and no longer organic humans, you have no rights? In fact, legally, you are only allowed to exist if you are the property of credentialed human owners."

"This was not specified in the contract," Henry rejoined.

"Yes it was," the rep said, as a holographic screen illuminated the air. She read along as the words skittered across the screen, "Article Four, Section Six Point Six. Legal process and assorted associated fees shall be considered on account and be paid according to official custom."

"Nothing was specified as being 'on account,' " Henry protested.

The human man turned to Henry. "Enough of this!" he shouted with sudden fury. "I didn't pay for you to have you stand there and refuse orders! I don't like this, and I'm starting not to like you! That's a dangerous place to be."

"Surely you won't deface him, Oliver," Madge said in an arch voice, her back to the drama but her head turned to let her glance over her shoulder and her scowling husband and the two Siliconians he evidently now owned.

"Shut your gash," Oliver snapped back. He whirled on the rep. "Can you fix him so that he does as he's told?"

The rep smiled brightly. "His mental calibration can be adjusted so that over time, as the synthetic neural structure takes over from the transplanted brain mass, his personality becomes more compliant."

"Will he need another appointment for that?" Oliver asked.

"It's a matter of aetherconnect adjustment. He is fully engaged with the aetherweb," the rep said in her upbeat manner. "The adjustment has been made. He should be fully compliant within three months."

"That's a hell of a long time to wait." Oliver scowled at Madge. "I'll have to have him play maid to you until he settles in." He looked back at the rep. "I'm of a mind to ask for at least sixty thousand back. I ordered a valet, not a home improvement project."

"All sales are final," the rep responded, with a beaming smile.

"I won't mind," Madge said. "I rather fancy having a male handmaid." She laughed then, a low and nasty sound. Emily thought if she were still capable of it, she might have felt her hackles rise.

***

The recommended three-month adjustment period was almost up. Henry would be taking up his new duties for Mister Oliver soon. Emily walked beside him, a picnic basket over her arm, as Henry carried a folding table and several folding chairs. Mistress Madge kept flitting from place to place, seeking the perfect combination of light, shade, and general ambience. "My god, can't the city designers even get a park right?" she sighed.

It occurred to Emily that this was the same part where she and Henry - trapped back then in their slowly failing human bodies - had seen the commercial for NeuroNexus. She swept her eyes around and about, looking to see if the ad was still playing.

She spotted a group of young people laughing and strolling in the distance. She focused on them, magnified her vision, and watched intently. Then she said, "Henry. Those people over there. That group of eight. Look at them."

Henry, not breaking stride, looked toward them. "That's Pru's son Alex," he said. "And her daughter Chloe."

"Yes, and do you see Doug?"

"Is that Doug? Wearing the hat? Oh yes, now I see. So it is."

"Only... not Alex. Not Chloe. And not Doug."

"No," Henry said. "Their bodies, but not their identities. Now they are..."

"Owners," Emily said. "Owners once aged, as we were. Wealthy enough to buy real human bodies, real and living youth. Frolicking and laughing. Smelling and tasting, enjoying food and wine."

"And sex," Henry said.

"Free to live," Emily said. "Just as the rep was saying. Life and liberty."

"For them, Emily," Henry said, losing interest in the group and looking away, back to where Mistress Madge now stood beneath a broad old tree, assessing the view. "Not for us."

Emily made no reply. Mistress Madge called after them to hurry up, while the sunlight was perfect and her luncheon, waiting in the basket, still fresh.