July 29, 2022

Queering Cinema: Dirk Bogarde in 'Victim'

Robert Nesti READ TIME: 5 MIN.

In 1960, Dirk Bogarde was at a crossroads. He was England's leading romantic male star throughout the 1950s – a British Rock Hudson. But had just ventured to Hollywood at the end of the decade with disastrous results, playing Franz Liszt in a poorly received, expensive biopic. Nearing 40, he could have likely remained a light, comedic actor, as he was in the hugely successful "Doctor in the House" series, instead, he took a daring role that invited inquiries into his private life: the sexually conflicted barrister in "Victim" (1961).

It was a role already turned down by James Mason and Stewart Granger, but for Borgarde turned out to be a career-changing performance that ushered the serious phase in a career that would last another three decades. Throughout this phase, Bogarde played numerous gay-shaded roles in films by Joseph Losey ("The Servant"), Luchino Visconti ("Death in Venice"), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder ("Despair"); but none hit Bogarde as close to home than that of "Victim."

That is because Bogarde lived openly with his business manager, Anthony Forwood whom he met in the early 1940s. Forwood left his wife, actress Glynis John, in 1946 to live with Bogarde and they were together until Forwood's death in 1988. But despite having published a nine-volume autobiography, Bogarde always described his relationship with Forwood as "platonic," despite friends and family members saying otherwise after Bogarde's death in 1999 at the age of 78. Bogarde convinced the world that his relationship with Forwood was purely professional, and to insure that he famously burnt his personal papers at the time of Forwood's death. But a series of 16mm films (shot by Forwood) were found after Bogarde's death and became the basis of a BBC documentary that all but outs him. His lawyer, Laurence Harbottle, said, "I share the view of every friend of his whom I have ever known – that Dirk's nature was entirely homosexual in orientation."

Perhaps he chose to play Melville Farr, "Victim's" conflicted barrister, because his character may desire men, but never acts on them; and, in the end, returns to his forgiving wife, Laura, played by Sylvia Sims, promisingfidelity. Or that audiences would not see the connection to his private life. Whatever the reason, no doubt his stature gave the film the star power for its subject – the abuse of homosexuals at a time when it was illegal – to be taken seriously. That Forwood and Bogarded lived outside the law is thought to be the main reason why he never came out during his lifetime, despite having lived some 32 years after 1967 Sexual Offences Act was passed. That law made homosexuality legal and came in part due to the impact of this film. It was famously the first film in which the word "homosexual" is said on screen, which led to censorship issues in both Great Britain and the United States. Bogarde later acknowledged the film's importance both to himself and the public. "It was the wisest decision I ever made in my cinematic life. It is extraordinary, in this over-permissive age, to believe that this modest film could ever have been considered courageous, daring or dangerous to make. It was, in its time, all three."

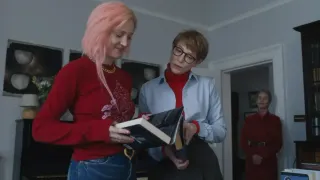

The film, directed by Basil Dearden, is a Noirish thriller about blackmailers targeting gays in London's West End at the time when gay men made easy prey for criminals. "Someone once called this law against homosexuals the blackmailer's charter," says one character. One target – a young cashier at a construction company – is arrested for embezzlement, but refuses to tell the police the reason for the blackmail and kills himself in jail. He does so to protect the identity of Farr (Bogarde), a rising talent in British legal circles whom the young man (named Boy Barrett, played by Peter McEnery) crushes on. It was a photo of the pair at the moment Farr broke off their relationship that provided enough of a reason for blackmail.

Farr feels responsible for the young man's death, in part because prior to arrest, Barrett had reached out to Farr. Thinking blackmail was behind the calls, Farr told him never to call again. He is drawn into the case when the police discover a notebook of clippings the boy kept of his career; which he carefully explains it away. It proves harder to explain with his wife, Laura, who knew of a similar experience from his past. Farr claims the relationship with Boy is chaste, which may be true, but Julia sees right through him: chaste or not, Farr is gay.

The film is certainly didactic in expressing its outrage at the treatment of LGBTQ individuals in England over the first part of the 20th century. Its suspense plot is often interrupted with commentary by minor characters who express their views about homosexuality. "Well, it use to be witches. At least they won't burn you," one character tells the distressed Barrett. Others express more homophobic attitudes. Gay slurs are heard throughout, even seen in print at one point when one is painted on Farr's garage door. But the overall tone of "Victim" is sympathetic, with the film's villains a pair of reprehensible thugs: he's a pretty boy sociopath, she's a nasty homophobe who deludes herself into thinking she's doing the public good through blackmail.

As Margaret Hinxman notes in The Guardian at the time of his death, like all the "most mesmerizing screen actors" Bogarde "could convey a quality of stillness which suggested hidden turmoil and torment." It is this quality of stillness masking hidden torment that is most memorable about his performance in "Victim" – concerned with what is furtive and hidden. Bogarde plays with these tensions, ultimately turning them into self-revelation. Whether he was sending a coded message about himself was never learned.