October 11, 2022

New Doc Goes Inside the Life of Trans Actor/Activist Georgie Stone

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 13 MIN.

The government has found endless ways to complicate the lives of transgender youth and deny the validity of their identities. Restrictions of the uses of school restrooms and locker rooms. Courts and governmental agencies interfering in medical decisions that should be between qualified health care providers and their patients. Parents threatened with having their child taken away for trying their best – and then doing even better – to support their gender identity.

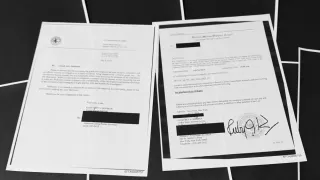

All these things have become daily horror stories from our national headlines, but years ago they were the daily life of Georgie Stone. Now 22, Georgie was 7 years old when she began to dress and outwardly identify as the girl she'd known herself to be since she was a toddler. She suffered bullying; her parents ran into bureaucratic brick walls; and, as adolescence approached with its implications of her body developing in ways that would estrange her even more from her own physiology, Georgie sought to access puberty blockers, a safe and well-understood treatment that can buy valuable time for transgender children. At the time, Australian law permitted the use of puberty blockers only if a court gave its permission. As a tight-knit family, Georgie, her twin brother Harry, and their parents, actors Greg and Rebekah Stone, took on the system – and won.

The battle was far from over. Though they succeeded in changing the law, it was still necessary to trans youth in Australia to get a court order to be permitted to undergo hormone therapy – the next phase in Georgie's gender affirmation treatment.

Far from the horror stories of "child abuse" and "child mutilation" perpetuated by anti-trans pundits and activists, medically appropriate gender affirmation treatment does not involve surgery on children, and the gender affirmation of transgender youth is a gradual and carefully supervised process. There's no such thing as "sudden onset gender dysphoria," but – to the deep, agonizing cost of thousands of trans youth – there is such a thing as ignorance substituting for medical expertise, and politicians trading the well-being of children for cheap, quick political gain.

Now a successful actor herself, Georgie – still with her family's support – continues the fight for fact-based understanding and compassion when it comes to how trans people are treated. Documentary filmmaker Maya Newell – who made the influential movie "Gayby Baby," about Australian kids growing up in families headed by same-sex parents, as Newell herself had – spent years with Georgie, witnessing her unfolding story and reviewing home movies, eventually creating a half-hour film, "The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone," that takes a deeply personal look at Georgie's life. Commencing on the day of Georgie's gender confirmation surgery – again, a procedure only allowed once Georgie came of age – the film shuttles back and forth in time, tying together the strands of Georgie's experience as an activist and a developing young woman faced with daunting challenges. But Georgie is not daunted; rather, she's gracious and strong, even when this piercingly honest portrait shows her at her most vulnerable.

Georgie Stone and Maya Newell chatted with EDGE about Georgie's lifelong advocacy for herself and other transgender youths, how the film came to be made, and the things that Georgie, despite all her successes, still wishes people would simply try and understand.

EDGE: It's beautifully put together in the ways you combine home movies from years ago with new footage that you've taken.

Maya Newell:: What was really lovely with this film is that it was this exploratory journey over many, many years, and we definitely didn't know what we were making when we set out. At a certain point, we landed on this idea of falling in and out of George's memories, and all the moments that make us as humans. Georgie is a creative producer [on the film], so when we got into the edit she was in there having story conversations with the amazing editor Brian Mason and producer Sophie Hyde, and we would be working out how we could weave and thread this story together. Georgie is a deep thinker and is incredibly insightful. There wasn't any lack of footage of Georgie contemplating her next move, which made it very easy to edit [toward] this beautiful concept.

EDGE: It's very commonplace for transgender children to know their true gender at a very young age and try to express this. Do you have an early memory, Georgie, of knowing that your gender was as a girl, and knowing that you had to try to explain this to people?

Georgie Stone: I think I remember the moment. I was two and a half years old. I think I'd been watching movies or reading stories, and I knew that I always identified with the female characters. I think it was bath time, and I was telling my mom that I was a girl. That's who I was. I was very adamant about it. At that point, you know, I hadn't had learned societal expectations of who we were, I didn't see it as a problem. It was only once I started school, when those binary ideas were kind of pushed onto all of us, when I realized that not everyone was gonna be accepting of me or understanding – and also realizing that adults didn't really listen to kids. I think that was when I realized that there would be a real uphill struggle.

EDGE: Parents of transgender children often describe a grieving process where they feel they've lost a child of one gender before they become accepting of their child as having another gender. Did your parents and your brother go through that sort of grief?

Maya Newell: There was one moment in the film where [Georgie's brother] Harry talks about how he really didn't seem to grieve. He was just very excited to have to have a sister.

Georgie Stone: It is a beautiful moment, and I think that really encapsulates my brother's reaction. For Harry there wasn't much of a process of grieving, necessarily, because it was always clear that I was still going to be really close to Harry, and we were still going to play, and we're still going to create stories together. Harry knew that that wasn't going to change, and that was the most important thing for him.

My brother was one of my earliest advocates. He was the pronoun police; he corrected other people on what my pronouns were, which was great.

For my parents, it definitely was a bit more of a period of adjustment. With my mom, she really just wanted to learn what this was and how she could support me, and she did a lot of research. They waited a few years just to see what would happen, because I was quite young. [They] let me let me play, let me dress up, let me really explore who I was at home. But it took a few years for them to realize that this was more than just playing – that I was who I said I was. And at that point, with the research my mom did, she realized that the only way she could lose me was to stop me from being myself; the only real grief that would happen was if I was incredibly unhappy, and [she realized] that I could be who I was. And [she understood] that supporting me was, for me, a life or death situation. If I couldn't be who I was, my life wouldn't be worth living.

For my dad, all he really wanted was for me to be safe and to be happy. Once he got his thinking towards the realization that the best way to support me and for me to be safe was for me to be myself, then he fully got on board. There was definitely a process of adjusting, but once I transitioned, I didn't see any grief with them, because suddenly they had a happy kid on their hands, and that's what was most important for them.

Maya Newell: One thing just to add to that, is that what's really beautiful about this film – and, in some ways, what is hard to access in lots of the other stories that we've seen – is that this story spans 19 years of George's life. That archive is a real gift to the public, but also to Georgie, to be able to see herself through the years and to see that consistency of self and [see] that transitioning isn't something that just happens quickly overnight, like lots of people would like you to believe. You see Georgie's consistency since she's a small child, and [gender affirmation] is something that families talk about and consider, and doctors support.

EDGE: Georgie has been so active for so long in working to change the laws in Australia regarding how transgender youth and their families were allowed to proceed with what they knew to be necessary, in partnership with their medical providers. At what point, Maya, did you say, "I need to make a documentary about this person and her story!"?

Maya Newell: Actually, I met Georgie when she was 14 and had had only just begin doing things publicly in terms of advocacy.

Georgie Stone: At that point I'd done [Australian current events program] "Four Corners," but because the court wouldn't allow us to identify ourselves, my mom and I had to wear prosthetics and wigs, which is hilarious. So, we changed the law, but all people knew was that there was [an important court] case. [To Maya:] When you contacted us, you didn't know that we'd done that.

Maya Newell: I contacted Georgie and Beck to explore making a film, [after] I had just finished making "Gayby Baby," my first feature. That was about children growing up in queer families like [my mothers'].

Obviously, the experience of trans kids and "gayby" kids is completely different, but the commonality is that lots of adults, public figures, politicians were talking about us, and for us, about the issues that would impact us, and telling us we would be damaged by our families in some way. You're being used as political fodder to push a political agenda. What was very powerful in making "Gayby Baby" was that those children spoke truth to power. They shared their stories, and the film gave a platform that really shifted the conversation in Australia from speaking hypothetically about children in queer families to acknowledging our existence in the marriage equality debate.

I [reached out] to Beck and Transcend Australia, the amazing organization that Georgie's mom created to support trans young people and their families, to find out more and learn more. We didn't go in with a hot idea of what I wanted to make. I just arrived on Georgie's front doorstep with a camera and did an interview. Georgie had braces and was 14, and just told me everything going on in her life, and we built a relationship over many years.

I do believe in the beauty and the honesty of children to be able to speak their truth and access something in the minds of adults. I think we harden as we become older, and it's beautiful to be reminded of the vibrancy and truth that young people offer.

EDGE: I have heard transgender people say that having to explain themselves over and over again, and having to push back against the fantasies people project onto them, is exhausting. Has that been your experience?

Georgie Stone: I am so exhausted. There was actually a moment around two years ago, when I turned 20, I remember saying to my mom, "I'm so tired. I'm 20; I shouldn't feel this tired." I should be going out and partying and being young and all of that kind of stuff. Being a trans person in this world, and the constant feeling like you're on guard, or you have to fight or explain yourself, or just looking at the news and seeing the way in which our community is targeted, and the way trans kids like me are thrown under the bus constantly, or used as political fodder... the constant fear about relationships and wanting to be open with people, but also being scared for your life... it's exhausting.

And then, on top of that, the advocacy I've been doing for years, and the sort of professional advocacy and fighting for rights and everything that came with that, and telling my story over and over again... [I'm] so exhausted. And there have been many times where I've felt that maybe I want to take a step back and just live in my own life for a while and do things for me. And there have definitely been times where I have done that, but I suppose what keeps me coming back to it all is how I genuinely believe that storytelling is one of the most powerful tools we have. And also, I remember how isolated I felt as a kid because I couldn't see anyone like me. I realized the power of visibility has, and not everyone wants to, or is in a position to, do that. I am in a position to do that. In some ways, I feel like I definitely grew up feeling like I had an obligation to do it.

I do believe that there is too much pressure on trans people to be the ones to have to explain things to everyone. I don't think that should be the case. The pressure should not fully be on trans people. I believe our voices should be listened to, and our voices shouldn't be drowned out. But I also think that we should not be standing alone, and there needs to be that support behind us. And there are ways to do that. You go to the Dreamlife website – little plug there. [Laughter] There are resources and places in which if you want to do that work with us, you can educate yourself and support us.

EDGE: There was a moment in the film, in the archival footage, where you're about 10 and you're asked what you wish people would understand. You say words to the effect of, "I really am a girl, and I'm not a boy pretending to be a girl." As time has gone on, has that remained the primary thing you wish people would understand? Has your wish expanded to include other things?

Georgie Stone: I suppose it has definitely expanded, but that point is still probably at the top of the list: That we are who we say we are, that we're not pretending, that we're not tricking people, that we actually know ourselves. Trans people are forced to do so much soul searching, and we're forced to look inwards all the time, and we're forced to justify ourselves all the time.

I think a lot will change if people actually just listen to us. I think nine-year-old Georgie had it right. And that's still one of the most important things, because people still don't get it; people are still just stuck on that [one point].

There's a lot that people needed to be educated on. People need to know that they don't have a right to ask about my body. Really, really personal, quite creepy things about my body that people somehow feel they are justified to ask about. It's incredible the [number] of old men who asked me at 16 if I'd had the surgery or not, what genitals I had, you know, that kind of stuff. It is awful, but people still think they have a right to know. I think that's another thing that people should know to back off from.

Maya Newell: But the great thing about making a film is you can just say, "Watch my film." Any questions? "Netflix."

EDGE: Definitely, everyone needs to see this film.

Georgie Stone: Yeah, I hope so. Yeah.

"The Dreamlife of Georgie Stone" is streaming now at Netflix.