January 3, 2023

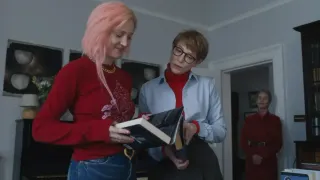

Queering Cinema: When Joan Met Steven

Robert Nesti READ TIME: 6 MIN.

"Objet d'art number two: a portrait. Its subject, Miss Claudia Menlo, a blind queen who reigns in a carpeted penthouse on Fifth Avenue–an imperious, predatory dowager who will soon find a darkness blacker than blindness. This is her story..."

Such reads Rod Serling's introduction to "Eyes," the second and most famous of the three sections to "Night Gallery," a made-for-television anthology film. When it premiered in November, 1969, Serling was a television icon for hosting (a la Hitchcock) the supernatural anthology series "The Twilight Zone" for five seasons earlier in the decade. That show had a troubled history – it was twice canceled by CBS and Serling, who, as well as hosting, produced 156 episodes wrote 92, was burnt out by 1965 and welcomed its final cancellation.

But four years later he was back in the game, using this film as a pilot for a new anthology series, also called "Night Gallery," that used Serling's format of stories set around paintings in an art gallery that were introduced at the onset. The show ran for three seasons with Serling again providing hosting duties. It would be his final project. One of early television's pioneers, he died young at 50 from multiple heart attacks. Known to smoke four packs a day, he was famous to be holding a cigarette in each introduction.

To direct the introduction to "Night Gallery," he chose a young director just getting his start at Universal: Steven Spielberg. The 22-year-old director had been hired by the studio (under Serling's guidance) to direct one of the film's three segments, the aforementioned "Eyes," that would bring him face-to-face with Hollywood legend Joan Crawford, who had been signed to star in the half-hour film.

That enough makes "Night Gallery" worthy of being considered Queer cinema, but added value comes with the film's first section, entitled "Graveyards" that appears to be a long-lost effort by Tennessee Williams. To begin with, it stars Roddy McDowell, who, though not publicly out, was well-known to be gay in the movie community. In it, McDowell plays the scheming nephew of a wealthy artist, a stroke victim unable to speak. When he realizes he will inherit his uncle's estate, he sets out to murder his uncle; but he must also deal with his uncle's long-standing butler (Ossie Davis), who has a plan of his own to take care of the venal McDowell. There is certainly the sense that Davis may be gay, especially when he's seen with another artist who looks like he walked out of "The Boys in the Band." At this point, the gay subtexts jump to the surface.

But "Graveyards" isn't what makes "Night Gallery" such a queer classic. Rather it is "Eyes" starring Crawford in her last professional acting role. Given the title, the irony is that Crawford's character, super rich Claudia Menlo, is blind, living alone in a Fifth Avenue apartment building and terrorizes anyone who comes in contact with her, including an eye doctor who may have a technique that could restore her eyesight, if only for a brief period of time. The rub is that the operation requires a set of good eyes from a donor who would lose their sight in the process.

The role of Menlo is fit for Crawford, who is elegantly coiffed in her splendacious Fifth Avenue digs. Unlike her film roles at the time ("Beserk" and "Trog"), this one returns her to the classic movie star persona and setting she tirelessly curated over her almost 50-year career. And Spielberg, working with cinematographers Robert Batcheller and William Margulies, honors that legacy, filming Crawford with a reverence (and wardrobe) that evoked her years at Warner Brothers in the late 1940s. She was royalty and Spielberg and company had no problem treating her as such.

Though if Crawford had her way, Spielberg would have been pushed off the project. He got the gig when Side Sheinberg, Universal's VP of Television, signed the young, 23-year-old Spielberg to a television contract after being impressed by his 1968 short film, "Amblin'." But Crawford balked – she didn't want an unknown director at the helm and complained to Sheinberg. Fortunately, Sheinberg talked Crawford into it; and the star and the young director got along famously over the eight-day shoot and kept in touch right up until her death in 1977.

In remembering working on the film with TCM's Ben Mankiewicz, Spielberg said that Crawford was a consummate professional throughout the shoot. "She was not Mommy Dearest. Let's put it that way. That was not my experience. She was kind and she was understanding."

He continued. "She was very, very elegant. And she was selling Pepsi Cola left and right. She brought huge, huge ice chests with Mountain Dew and [Pepsi] and every single day, gave it to the crew and she said if you don't belch after drinking, it's an insult." Crawford had married Alfred Steele, the last of her four husbands who was CEO of Pepsi Cola and led to her tireless involvement in the company and advocacy for its products.

Spielberg later said that he respected her because she treated him as if he knew what he was doing. "And I did not know what I was doing," he joked to Mankiewicz "I had never worked with a crew that size before."

Crawford's icy persona helps make at least the first half of "Eyes" compelling viewing. As conceived by Serling, she's a character not far removed from the malicious Countess from Friedrich Dürrenmatt's "The Visit," a popular melodrama of the time later turned into a Kander and Ebb musical. And Crawford doesn't flinch at playing mean to the hilt. Also being blind, the role gives Crawford a chance at portraying a person with a disability with steadfast determination. It was Serling who let both his star and director down with a gimmicky script that is likely why the film is seen as camp today.

Still, Spielberg directs with flair, breaking many of the established rules of television in the process, as well as looking forward to many of the techniques he would develop over his long career. How he became a film director is the subject of "The Fabelmans," his autobiographical film that looks back at how he became a moviemaker, which is short-listed for a Best Picture Oscar this March. To see how he started his career, and how Joan Crawford ended hers, seek out "Eyes." Even towards the end, she was always ready for her close-up.

Watch Steven Spielberg talk about directing Joan Crawford in "Eyes":