October 3, 2018

The True

Brooke Pierce READ TIME: 3 MIN.

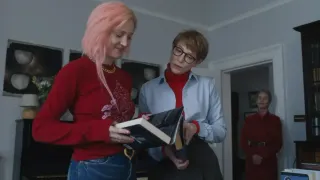

With the New York State primary just behind us, and November midterm fever well upon us, now is a perfect time for Sharr White's new play "The True," being presented by The New Group under the direction of Scott Elliott. Set in Albany in 1977, this engaging comedy starring Edie Falco looks at the local party politics of yesteryear and how its operators struggled with changing times.

Much of the play takes place in the homey living room of the Noonans, which Erastus Corning II (Michael McKean) visits almost nightly, sitting next to his dear friend Peter (Peter Scolari) in front of the TV in a cozy armchair. As the mayor for 35 years, Corning is a man with a lot of power, but it's the woman sitting behind him at a sewing machine that can take credit for much of his success. Not with an important formal title, but as a party loyalist and confidant, Polly Noonan (Falco) has been nurturing his career since the 1930s.

The trouble now, though, is that, with the party chairman recently deceased, Corning has to worry about being challenged by his frenemies from within the ranks. And yet, just at the time when Polly's advice and strategic thinking would be most valuable, Corning pushes her away, saying that he needs to end his association with her. Is it because he wants to swat away the persistent rumors that he and Polly are having an affair, or for some other reason?

Even after being given the cold shoulder from her longtime friend, Polly – played with an endearing frankness by Falco – can't suppress her instincts. She takes it upon herself to meet with the men who want to usurp Mayor Corning in the hopes of stopping the coup, and also endeavors to get a promising young man a committeeman position because she's anxious to see some "young blood" injected into the party. Time and again she is disturbed by the lack of loyalty she sees: Why are other party members being disloyal? Why do up-and-comers seem incapable of showing the same amount of dedication and loyalty that she always has?

Playwright White's political-insider dialogue is effortless and authentic, but not off-putting or overwhelming, largely because the play focuses on people, not issues. On paper, a character like Polly – with her big personality, foul mouth, and obsessive political maneuvering – might make one think of the often-derided corrupt cronyism of old-school New York. But in flesh and blood she feels like a regular person who just wants to take care of her community.

Today, as Democrats are rebelling harder than ever against the party machine, "The True" ends up being a counter-argument. It's not a full defense of the machine, but an acknowledgement that "party loyalty" and "doing favors" could be seen as synonymous with helping people. Polly is the champion of a system that had traditionally ensured that politicians knew all their constituents and their needs personally – and perhaps it takes party loyalty and a machine to make that happen.

It's understandable if you may be thinking "I can't take any more politics!" at a play, or anywhere else for that matter. But "The True" is not just about politics, it's about relationships. Indeed, the very notion that Polly labors to defend is that politics is relationships. To her, it's about commitments – commitments to constituents, to allies, and to friends. The play will leave you hoping that it might be possible to find a way to fight Albany's corruption (which is still endemic and infuriating to this day) while retaining the loyalty and conviction of a Polly Noonan.

"The True" runs through October 21 at The Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd Street , NYC. For information or tickets, call 212-279-4200 or visit www.thenewgroup.org